The Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme, or The Somme Offensive, was a battle of the First World War, fought from 1st July to 18th November 1916 by the armies of Britain and France against Germany. The attack took place at the point where the British and French Armies met, a 25-mile front along the River Somme in Northern France.

Initially an operation meant to be led by the French Army, the German attack at Verdun on 21st February earlier in the year meant that role of the British Army, consisting primarily of inexperienced men who volunteered at the outbreak of war, was greatly increased, with the French adopting a much reduced role. The Somme became vital in reducing pressure on the French by pulling German reserves North and away from Verdun.

Beginning with a 7-day artillery bombardment, in which over 1.5 million shells were fired, and the detonation of mines beneath the German lines, British generals were confident that the German defences would be shattered by the attack, and the British troops would be able to simply walk into the now vacant enemy trenches unopposed. Such a devastating attack would see the German centre broken, allowing the Cavalry to be brought up to exploit the gap and roll up the defensive line.

Despite such optimism, the first day on the Somme, 1st July 1916, is remembered as the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army, which suffered a staggering 57,000 casualties, a third of whom were killed. Emerging from their trenches at 7:30am, British troops were confronted with uncut German wire. The bombardment proved insufficient; the strength of the German lines was underestimated and British forces largely failed to break through. On top of this, British artillery outpaced the troops, allowing the Germans to emerge from the safety of their dug outs and man their machine guns, greeted by thousands of enemy soldiers floundering in No Man’s Land.

Only in the South were substantial gains made, where troops of the 18th and 30th Divisions, fighting alongside the French 20th Corps, captured all of their first-day objectives. This was largely owing to the use of French artillery batteries in this sector, which proved superior to the British in their ability to cut barbed wire, as well as the fact that the Germans did not expect the attack to reach so far South.

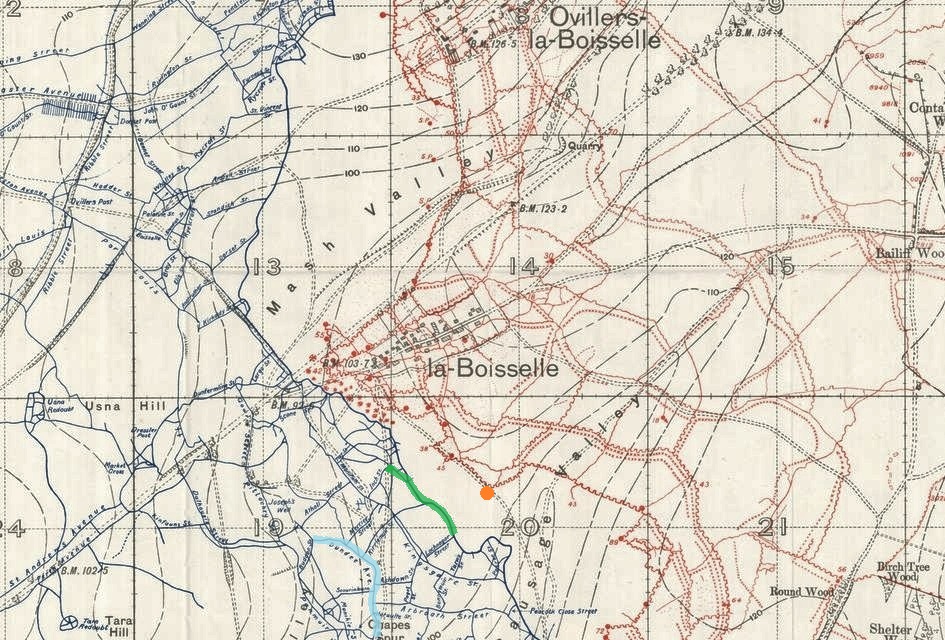

This following timeline chronicles the first four days of the offensive from the point of view of the 9th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, who began the 1st of July in reserve at Albert. In support of the 34th Division who attacked at 7:30am, the 19th (Western) Division (of which the 9th Cheshires were a part) were rushed forward in case of a German counter-attack when the failings of the initial attack became clear. The Battalion played an integral role in the subsequent capture of the village of La Boisselle, which ultimately fell into British hands on 6th July.

Saturday, 1st July

10am: The 9th Cheshires, held in reserve at the commencement of the attack, assemble on the TARA USNA line, between the Tara and Usna hills just East of Albert. Here, they are kitted out with tools and bombs in anticipation of being called into action.

7pm: Colonel Worgan, the 9th Cheshire’s Commanding Officer, is given orders during a Brigade HQ meeting to attack North Eastwards towards the village of La Boisselle at 10:30pm. The Battalion is to take up positions from LOCHNAGAR STREET to INCH STREET.

Moving through DUNDEE AVENUE, some men from B and D Company are separated from the Battalion and eventually end up making their way to Bécourt Wood, South of the British frontline. At this point in the day, after the largely unsuccessful opening attacks, communication trenches are blocked by masses of dead and wounded soldiers from the first wave.

9:40pm: The Battalion struggles to assemble amid the carnage of the attack. It is now too late for the proposed 10:30pm attack to take place, so the Cheshires consolidate their position and await new orders. Worgan sends Lieutenants Ward and King with the present members of B and D Companies to reinforce the Lochnagar Crater, which is being held by around 200 men of the 34th Division, who attacked earlier in the day as part of the first wave.

Sunday, 2nd July

2:30am: Brigade HQ orders the 9th Cheshires to prepare to attack La Boisselle. The men of B and D Companies separated at Bécourt Wood arrive at the frontline and are set to work on trench repairs.

4:00am: Orders are received: the attack on La Boisselle is to commence at once.

4:30am: The attack is launched in the “deathly quiet” dark and is successful, with the first line of German trenches captured. Too many men, however, now occupy these trenches, so C Company (Edwin Earl’s Company) is moved to reinforce the Lochnagar Crater.

4:00pm: Almost 12 hours after their initial attack, the Battalion receives orders to “bomb through” La Boisselle and clear any German dug outs found there. The village of Ovillers, to the North, is bombarded by British artillery in a successful diversionary attack. German artillery retaliates, leaving the attack on La Boisselle unharried. The Wiltshere Regiment’s 6th Battalion and the 9th Royal Welch Fusiliers make a frontal attack, with the 9th Cheshires attacking on their right.

The Cheshires advance under Lewis gun fire, with bombers sent on either flank in an attempt to clear the way forward, systematically bombing German dug outs. The destruction wrought by the British artillery and the “maze of trenches” makes it difficult for the men of the 9th Cheshires to keep direction. Some use a Russian sap, (a shallow tunnel dug beneath No Man’s Land which is ‘opened up’ during an attack by removing the top layer of earth), until it is eventually clogged with the bodies of the dead and wounded. Others run into unexpected obstacles, such as a deep and wide communication trench which holds up the advance.

8:30/9:30pm: By evening, the West of La Boisselle and its Southern defences are cleared. The 9th Cheshires consolidate their position.

Monday, 3rd July

2:45am: The Battalion receives orders to continue the attack, with support from 57th Brigade and the 9th Welch on the left and right flanks respectively.

3:45am: However, after an hour, no contact has been made with forces on either flanks. The 9th Cheshires attack via saps because of German machine gun fire raking the open ground, as well as the presence of four belts of uncut barbed wire. They fight their way into the second German line.

6:00am: A German counter-attack pushes the 9th Cheshires back to their starting point. The Battalion is able to reorganise and drive the Germans back.

The rest of the day is spent fortifying their position in anticipation of further German counter-attacks.

near La Boisselle, July 1916

Tuesday, 4th July

3:30am: The 9th Cheshires are relieved and withdrawn from the frontline.

6:30am: The Battalion returns to its original starting point on 1st July, the TARA USNA line. The men largely spend the rest of the day sleeping as roll calls are made.

By this point the 9th Cheshires have suffered 305 casualties, with 3 Officers killed and 10 wounded; 25 Other Ranks killed and 235 wounded.

34 men are listed as missing, one of whom is Edwin Earl, who was wounded on 2nd July and evacuated from the area of fighting.

Edwin suffered a “nasty wound in the right knee” as C Company occupied the German frontline trenches adjacent to the Lochnagar Crater. Despite this he was able to continue fighting with his unit late into the night. “Heavy hand-to-hand fighting” followed, in which Edwin received another wound, this time to his left foot. This second injury is described as a gunshot wound that passed through his boot.

As a result of these wounds Edwin was withdrawn from the line and was mistakenly recorded as missing until this was rectified on 6th July. He was then sent to a hospital ship at Calais where he was treated for 4 days before returning to England to be operated on in London, following which he spent at least 5 weeks recovering.

The Battle Continues

Despite such horrific losses, with the French still under attack at Verdun the attack on the Somme could not be called off. What followed was ultimately 12 separate battles of attrition fought up until November. By the end of the Battle of the Somme, over half a million soldiers on both sides had been killed, with around 10km of ground gained by the Allies. With a final, decisive victory unobtained, military elites on both sides realised that the First World War would likely be won by means of attrition rather than through a direct breaking of the enemy lines. As such, the Somme can be regarded as an important turning point in the war, where it became clear that Germany would struggle to overcome the materiel supremacy of the Allies.

Typified by its disastrous opening 24 hours, where the British Army alone suffered almost 60,000 casualties, the Somme has become a byword for the futility and slaughter of the First World War. However, the conflict also heralded new military innovations, such as the first deployment of the tank in September 1916, the growing importance of air power, and in large part brought about the professionalisation of the Pals Battalions, which would ultimately play a vital role in winning the war in 1918.